Independents Day: why local election results could be bad for development

Most analysis of the local election results across England earlier this month focussed on what they might mean at a general election. Whilst Westminster obsesses over a set of results which revealed nothing new on that score, an important story has slipped under the radar, and one which pits Sir Keir Starmer’s putative planning policy against an emerging but disparate local force.

Thursday 2 May was “independents day”.

In the 107 councils holding elections, the number of independent councillors - those not affiliated with any of the so-called major political parties - nearly doubled, from 135 to 228 council seats. To put that into perspective, the Green Party (who have a substantial national following and have since 2010 returned an MP to Westminster) won a total of just 181 council seats.

Independents also took overall control of Castle Point council (in Essex) from the Conservatives, taking the total number of England’s 316 local authorities controlled by independents to 11. That may not seem significant, but this will: in 45 local authorities independents are in decision-making roles on committees. For reasons that will become clear in a moment, another very significant fact: fully 80% (255 of 316) of England’s councils now have at least one independent councillor.

What’s the problem? Put very simply, independent councillors tend not to support development.

Analysis of approval rates, and time taken to decision, on major applications in England in the year prior to these latest elections is stark: independent-controlled councils rank bottom on both metrics.

Looking at the DLUHC approval data by type of major development, acknowledging that sample sizes are small, suggests independent-controlled councils have a particular problem with major dwellings, which is intuitive given the high incidence of the suffix “Residents Association” on independent councillors listed affiliations.

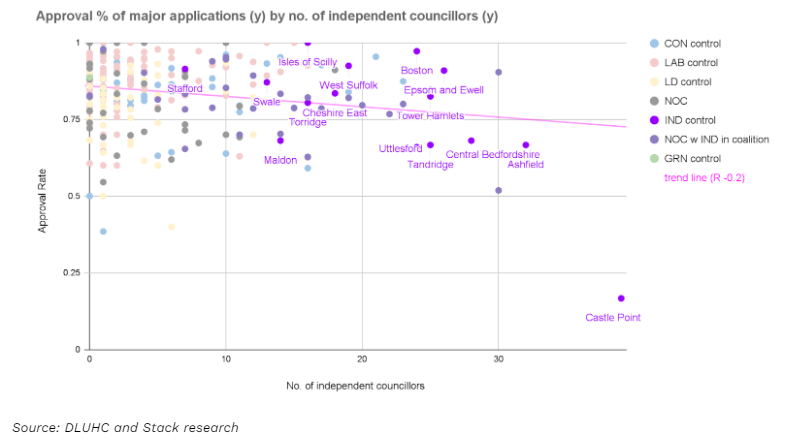

Beyond formal control, our analysis at Stack Data Strategy also reveals a negative relationship between the number of independent councillors and the approval of new developments. Put more simply, the more independent councillors elected in a given place, the fewer new developments proceed:

We might very reasonably conclude that this is evidence of the system working: candidates and councillors are responding to local preferences and delivering for their voters. In places like Castle Point that seems the right analysis, and as a developer it would be eccentric to expect speedy approval of even the best-designed development.

Meanwhile the country needs more housing, and also the infrastructure necessary to support a less carbon-intensive energy system. Take solar farms as just one example: the list of councils with a growing number of independent councillors overlaps substantially with the list of new solar applications being considered by the Planning Inspectorate. One in three councillors in each of North Kesteven, South Kesteven, South Holland, East Lindsey and Boston are now independents.

This is no counsel of despair: our research shows that there is underlying public support in Lincolnshire and elsewhere for new solar farms, and that public support can be won in most places if people feel their concerns and aspirations are being properly addressed. Public opinion is neither monolithic, nor static.

What does our research suggest those making the case for development should do?

First, speak to their concerns. We have run extensive message testing across the country to understand which arguments in favour of - and against - development resonate. Overwhelmingly, people respond positively to arguments about giving young people in their local area a chance to own or rent affordably, and to arguments about the jobs that development creates. Both of these arguments are particularly effective among those who are least supportive of development.

Second, describe exactly what, and exactly where, you’re proposing to build. A practical example from one of our projects in an authority on the edge of a major city: most people don’t really understand what the Green Belt is, and planning more generally is - like most professions - littered with impenetrable jargon that is off-putting to people. Labour’s adoption of the term “grey belt” is a very intelligent step forward in planning: our polling shows that simply pointing out that not all Green Belt land is actually green increases support for development. In the same project we’re finding that there is dramatically more support for private family housing, than for higher-density blocks of flats: speaking generically about “housing” doesn’t help.

Third, from that same project, and deliberative polling we’ve done for LPDF, support for developing the Green Belt itself rises substantially when we articulate potential benefits to respondents. For example, from a baseline of 32% supporting and 38% opposing, nationally, development on the Green Belt in their local area, we see those proportions flip when respondents are told that because of the costs of developing brownfield sites, it is often easier to deliver affordable housing on Green Belt sites: 38% then support developing their local Green Belt, and only 29% oppose.

I have spent the past decade measuring public opinion on all sorts of issues, in particular politics and planning, and the parallels are uncanny. In both politics and planning, the debate tends to be dominated by motivated and vocal minorities at the edges of opinion, and the majority of people - with neither the time nor the inclination to involve themselves - simply watch the words go by.

The crucial difference is that in politics there are regular, relatively easy opportunities to enter one’s view: elections. In planning, most people don’t know how to contribute, even if they wanted to: we polled young adults in England for LPDF in 2023 and found that 81% have never engaged with a local planning application, a number which if anything I suspect understates the reality. When asked why, 36% of respondents said they didn’t know how to, and a depressing 18% said they didn’t even know they could. Developers making a proactive case, grounded in an analysis of representative local preferences, will be a good starting point.

Whilst these local elections may represent a step backwards, we can unlock support for development, and get the country building the right things in the right places.

This article first appeared on ReactNews (£): https://reactnews.com/article/independents-day-why-local-election-results-could-be-bad-for-development/