Who can stop the Polish right?

Sign up here to receive our regular Election Note! Read the full analysis and receive the full version of each note as soon as it is published.

Published 24 August 2023

The Polish parliamentary elections of October 15th will be a tight race with large consequences for the EU. Will the United Right (PiS) secure a third term? Will Donald Tusk’s opposition take Poland back to a more pro-EU course? Or will, as many analysts expect, there be a hung Parliament? We show how the potential for polling error leaves all three possible outcomes in play in what is likely to be the most consequential EU election of 2023.

Key takeaways

Poland’s elections are the most important EU elections of 2023. A PiS defeat would create the opportunity for a reset in EU-Poland relations and allow the EU to move forward on key dossiers.

PiS is very likely to fall short of absolute majority. Although PiS are the strong favourite to win the elections, their odds of a parliamentary majority are slim.

Small polling errors could have large consequences for post-election politics. Polling error has plagued previous Polish elections. We show how error would affect the likelihood of each electoral outcome.

Why do the Polish elections matter?

The upcoming Polish elections of October 15th are arguably the most important elections of an EU member state of 2023. Over the last five years, Poland has become a more and more influential player in Europe. Firstly, its economy has proven surprisingly resilient amidst the series of economic shocks it has had to endure and has become a powerful asset to the EU market. Since Brexit, Poland has also adopted a more pivotal role in EU decision-making, not least because its relative voting power has increased since the UK’s departure. And lastly, Poland has played a major role in NATO’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Not only does the country serve as a main hub for supplying weapons to Ukraine, but it has also received the most refugees of any European member state.

However, as Poland’s international influence has grown, so have concerns about the state of its democracy. Over its past two terms in office, the Law and Justice party (PiS) has enacted a series of reforms that have been criticised by the opposition as well as Polish and EU experts for failing to adhere to EU and Polish constitutional law. Over the past years, PiS and the European Commission have repeatedly clashed over the state of the rule of law in Poland. The most recent dispute has centred on the PiS’ judicial reforms, but concerns have also been raised regarding press freedom, the rights of women and minorities, and potential undermining of free and fair elections.

All of this has negatively affected Poland’s relationship with the European Commission, which has launched a series of infringement proceedings against Poland for a failure of the member state to comply with EU law. The most eye-catching of these are the procedures around the so-called ‘disciplinary chamber’, which undermined the independence of the Polish judiciary according to the final ruling of the European Court of Justice. Since Poland has failed to comply with this ruling and suspend the chamber, the EU has levied fines of €1 million a day. The EU has also withheld billions of euros from the EU pandemic recovery and cohesion funds due to the government’s failure to address rule of law concerns.

This is exactly why these elections are so important. If the PiS wins an absolute Sejm (the Polish parliament) majority, as it did in 2019, these disputes are unlikely to be resolved soon. However, a victory for the opposition, led by former European Council president Donald Tusk, would create a window of opportunity for a reset in EU-Poland relations. In such a scenario, Tusk would reverse many of the reforms enacted by the PiS government and unlock the frozen EU funds.

What is the state of play?

Figure 2: Seat projections per party based on polling averages

Currently, the United Right coalition of PiS and its allies holds a relatively stable lead in the public polls and are expected to win approximately 38% of the vote (see Figure 1). Tusk’s Civic Coalition trails by 8 percentage points at 30%. The remaining votes are split between the far-right Confederation (11%), the centrist ‘Third Way’ coalition (11%) and the Left (9%). All parties have remained relatively stable in the polls over the course of 2023. The only exceptions to this rule are Confederation, which gained significant support in July but now appears to be sliding back down again, and Third Way. The latter has got some analysts worried, as Poland uses an 8% electoral threshold for parliamentary representation for coalitions like Third Way. Should Third Way drop by another 3%, it would lose its right to seats in parliament altogether.

As often, vote shares are not the full story. Polish MPs are elected in 41 constituencies with 9 to 15 seats each, and the electoral maths of the Polish system slightly benefit larger parties. So how do these vote estimates convert to seats? If we assume that the geographic distribution of each party electorate has remained unchanged since 2019 (the ‘uniform national swing’ assumption), we can use the national swing in polling to project the number of seats each party would win in each of these constituencies.

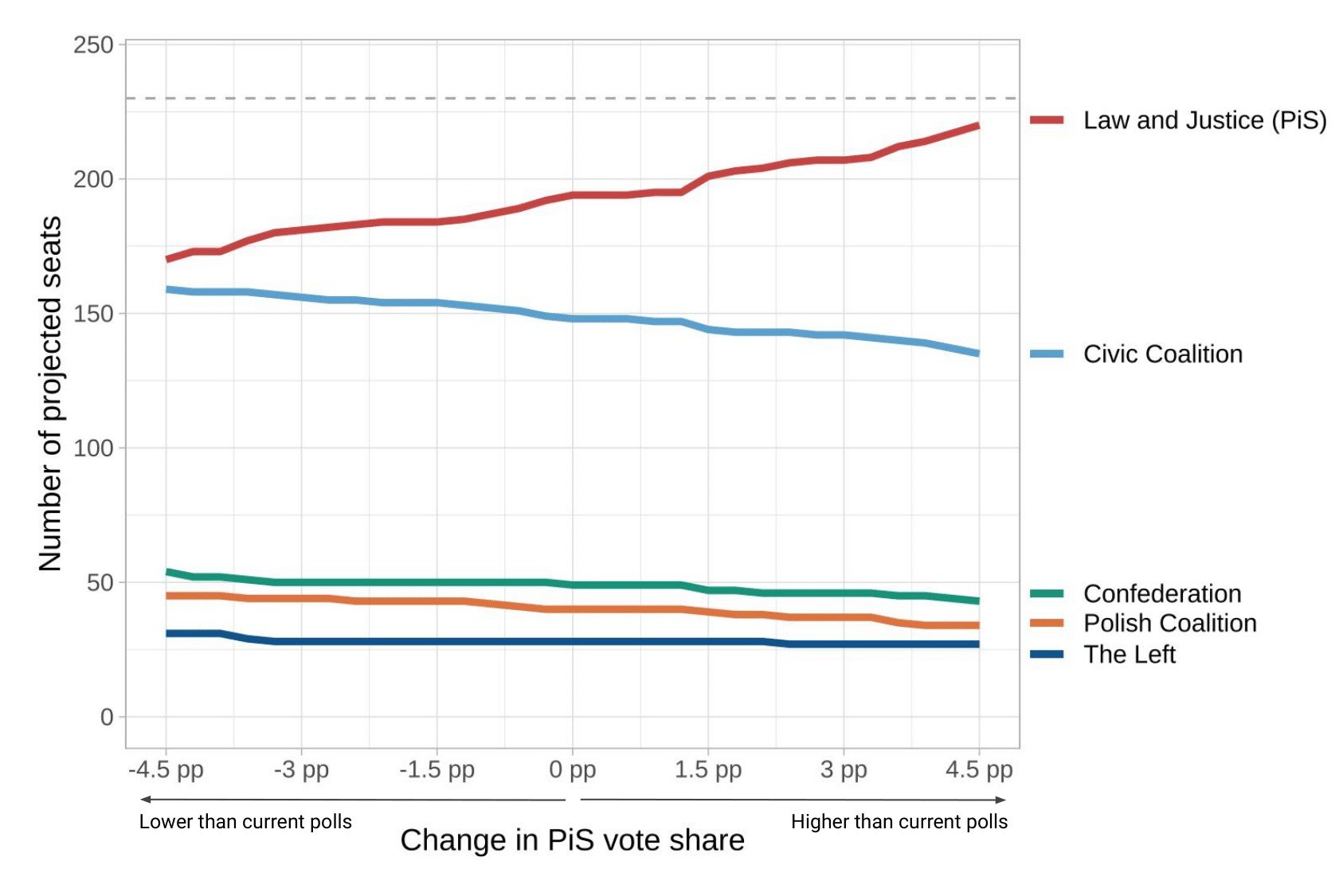

Figure 2: Seat projections per party based on polling averages

Figure 2 shows the aggregate results of this exercise. Under the current polling averages, PiS/United Right would win 194 seats, followed by the Civic Coalition with 148 seats. Importantly, this would imply that PiS would fall short of an absolute majority of 231 seats but could get there with the help of the additional 49 Confederation MPs. On the other side of the aisle, an opposition coalition of Civic Coalition, Third Way, and the Left would win 216 seats - 15 seats short of a majority.

What outcomes are most likely at this point in the race? Three results are in play:

PiS wins an absolute majority of at least 231 seats. This would be the most straightforward outcome. If this happens, PiS will have full control of government once again and the Polish status quo will remain. The problem with this scenario is that it is not very likely. As section three will illustrate, the polls will have to be very badly wrong for this outcome to materialise. Reminder: in 2019, PiS won a stunning 43.6% of the vote and only reached a narrow parliamentary majority of 235 seats.

PiS wins but falls short of an absolute majority. Given current polling, this is the most likely outcome of the elections. The open question is whether PiS would be able to find a junior coalition partner to reach a parliamentary majority. The most likely candidate is Confederation, but PiS leaders have openly said that they want nothing to do with Confederation. For their part, Confederation have also said that they want nothing to do with PiS, with some commentators believing that the party would much prefer to sit back and let the country sink into a political crisis before hoping to capitalise at the next election. In any event, coalition negotiations will be long and difficult in this scenario.

Civic Coalition wins but falls short of an absolute majority. This is the least likely scenario, and would require the polls to be off very significantly (see section 3). However, if this were to happen, there would likely be a path to a majority for CC together with Third Way and the Left. This would represent a major break with the Polish status quo and create the conditions for a reversal of the ongoing democratic backsliding and a reset of EU-Poland relations.

What if the polls are off?

Figure 3: Change in party seat shares by variation in the PiS vote

That leaves just one question: how reliable are current polls at predicting the election results? Firstly, it is worth nothing that the election is still more than 7 weeks away. Last minute shifts in vote intention are not uncommon and can significantly change the probability of the different outcomes. The other elephant in the room is polling error. In 2019, the polls significantly overestimated the PiS’ seat share while underestimating the number of seats won by the Polish People’s Party and the far-right (‘KORWIN’, now part of Confederation as ‘New Hope’).

Figure 3 and Figure 4 project the number of seats per party/coalition if, either due to volatility or polling error, the PiS vote share results would turn out to be different from the currently projected 37.9%. The range of the graph varies from an overestimation of PiS by 4.5 percentage points on the left (PiS gets 33.4%) to an underestimation of PiS by 4.5 percentage points on the right (PiS gets 42.4%). As before, the projections assume uniform national swing and that other parties are affected proportionally by PiS gains or losses.

Figure 4: Change in coalition seat shares by variation in the PiS vote

Firstly, Figure 3 projects the change in seats per party when the PiS gains or loses compared to current polling numbers. Two elements stand out. Firstly, even if the PiS ends up 4.5 percentage points higher than the polls currently estimate, they would still only win 220 seats (11 seats short of a majority). A coalition would be their only way to avoid a hung parliament. Secondly, the results would have to be drastically different from current polling if Civic Coalition is to win more seats than PiS. Currently, even if PiS drops to 33.4%, PiS would drop to 170 seats against CC’s 159 seats.

When it comes to potential coalitions (Figure 4), the electoral arithmetic is simple from PiS’ perspective. Unless they lose more than 3 percentage points (34.9%), they will have the option of reaching a parliamentary majority with Confederation support. For the opposition, the path to a majority is much more complicated. For the opposition to reach 231, PiS vote share will need to drop by at least 3.5 percentage points (34.4%). Significant voter shifts or large polling errors are necessary for that to happen.

In brief, what these simulations show is that PiS is very likely to end up as the largest party, even when taking possible polling error into account. The option of obtaining confidence-and-supply support from Confederation will be on the table, although these negotiations will be extremely difficult as discussed in section two. For the opposition to have a path to a majority, they will either need to realise substantial last minute gains or the polls will need to have significantly underestimated opposition support.