What the Locals mean for a UK general election

Sign up here to receive our regular Election Note!

Published 23 June 2023

In Rishi Sunak’s first electoral test as Prime Minister, the Conservatives suffered major losses in local elections across England. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Green Party were the main beneficiaries, gaining over a thousand councillors between them. These results undermine the developing narrative of a Conservative recovery, but questions remain about Labour’s ability to transfer mid-term success into a General Election. History suggests Labour’s polling lead will likely narrow before an expected 2024 election, but with a current lead larger than any opposition’s since 2009, it is an uphill battle for the Conservatives.

Key takeaways

Conservatives suffer historic losses in English local elections. The Conservative Party lost over a thousand councillors in Thursday’s local elections, exceeding even the most pessimistic predictions. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Green Party made substantial gains.

Although many analysts have claimed that the results point towards a hung parliament in 2024, we argue a Labour majority is still more likely. Labour’s projected lead over the Conservatives was larger than for any local election since 2001 and points to a majority-winning coalition. Three outcomes are in play and will depend on ongoing volatility, regional electoral maths, and possible polling error

Nevertheless, historic trends suggest Labour’s lead may narrow as the General Election approaches. Despite encouraging local election results, Labour’s lead is likely to narrow before the next General Election. Having already changed leaders, the Conservatives are relying on an economic turnaround to boost their chances.

England’s 2023 Local Elections

Figure 1: Net change in councillors by party, 2019-2023

The overriding story of the 2023 Local Elections is of major Conservative losses. Across England, the Conservatives experienced one of their worst ever local election performances. The party lost a third of its councillors up for election, along with nearly two-thirds of its majority-controlled councils. This is despite the fact that these wards were last elected, for the most part, in May 2019, another poor performance for the party. With some margin of error due to boundary changes, the Conservative Party went from over 5,500 councillors in these wards in 2015 to less than 2,300 in 2023.

The swing against the Conservative Party happened in almost all areas up for election - North and South, wealthy shires and working class towns, Conservative enclaves and strongholds. In “bellwether” councils with marginal Westminster constituencies, such as Plymouth, Swindon, Blackpool and Stoke-on-Trent, Labour won convincing majorities. In Conservative heartlands, such as Suffolk, Lincolnshire and East Hertfordshire, the party experienced losses to Independents and localist parties, as well as the Green Party. And in swathes of southern England, the Liberal Democrats overturned long-standing Conservative majorities. The biggest Conservative losses were seen in wealthier Southern councils, with the Conservatives losing all of their councillors in Lewes and the Vale of the White Horse, for example, both of which elected Conservative majorities in 2015.

Where there were exceptions to this pattern, it was due to highly localised factors. In both of the councils gained by the Conservatives - Torbay and Wyre Forest - it was off the back of gains from localist and independent groups. The most striking swings of the night were in Slough (Conservatives +16 councillors) and Leicester (+17). In Slough, the Labour-run council had been effectively declared bankrupt, while in Leicester 19 local Labour councillors had been deselected by the national party. It may be significant, though, that both Slough and Leicester have significant British Indian populations, and there is some evidence of a swing towards the Conservatives in areas with large Hindu populations.

The spoils of Conservative losses were shared between Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Green Party, each of which made substantial gains. Labour was keen to emphasise its performance in key targets for the next election, especially those bellwether councils mentioned above. The party also made substantial gains in areas not won since the 1990s, such as Medway, East Staffordshire and Bracknell Forest - one of the most surprising Labour gains of the night. Similarly, the Liberal Democrats were buoyed by their performance in Westminster target seats, hoping to assert themselves as the primary opposition to the Conservatives in so-called ‘Blue Wall’ constituencies. The party had emphatic victories in Westminster targets including Winchester, Guildford, Eastbourne, and Surrey Heath. Finally, the Green Party provided one of the most unexpected stories of the election, gaining 241 councillors, doubling the tally from 2019. The party won its first ever council majority, in Mid Suffolk, and became the largest party in Lewes, Forest of Dean, Folkestone and Hythe, Warwick, East Hertfordshire, Babergh and East Suffolk.

That all three of Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens won significant numbers of councillors from the Conservative Party speaks to an emerging anti-Conservative bloc of voters, willing to support whichever party is best placed to oust the Conservatives locally. For Labour, this is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, Liberal Democrat and Green campaigns draw Conservative resources to areas where Labour is far behind. Whether through formal agreements or not, centre-left coordination made all three parties’ votes more efficient. On the other hand, Lib Dem and Green success has laid the ground for difficult questions about coalition formation in the event of a hung parliament. While Starmer spoke of Labour’s path to a majority, journalists wondered what Ed Davey’s coalition demands might be.

What do the local elections tell us about the race for Number 10?

Figure 2: Projections of national vote share, based on the local elections

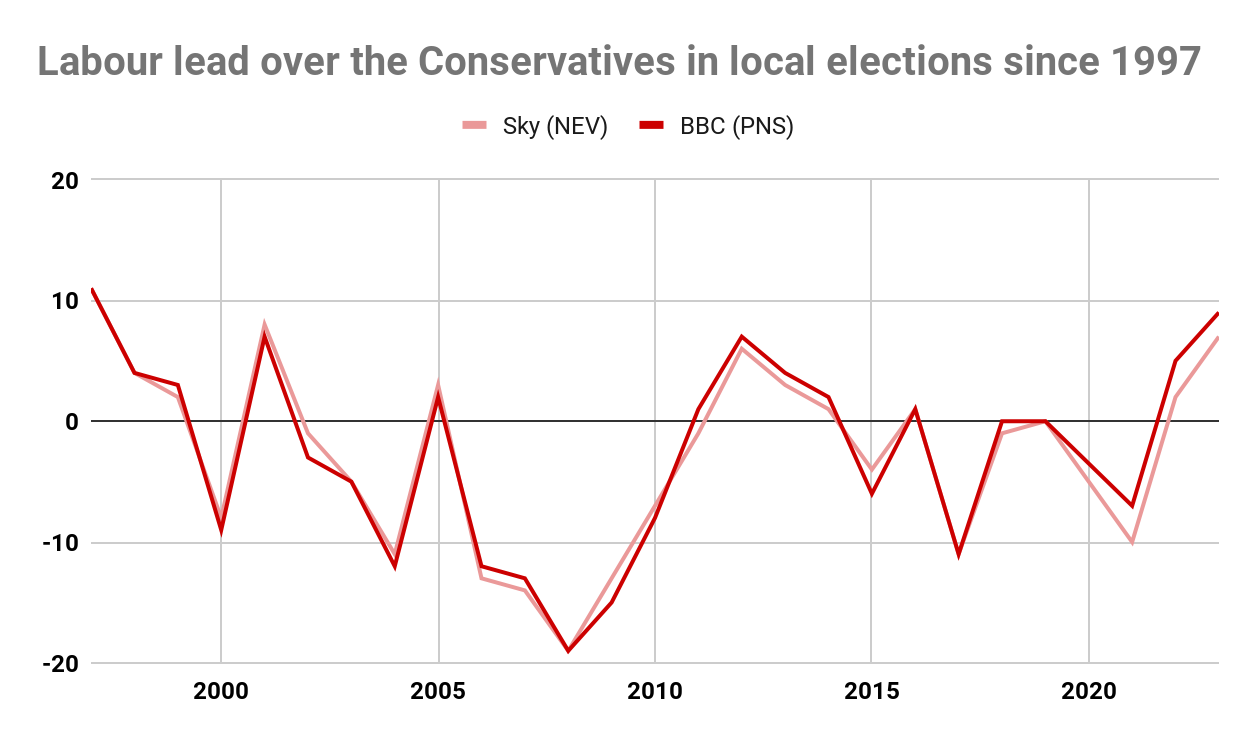

As always, pundits seized on the local election results to prophesy about the next General Election. In the days after the election, a consensus began to form that Labour had done well, but not well enough to win a majority at the next election. This assessment was principally based on Projected National Share (PNS)/National Estimated Vote (NEV) estimates produced by the BBC and Sky, showing Labour with a 7 or 9% lead over the Conservatives, respectively. This is much smaller than national polls showing a 15% Labour lead on average. Here, we present some reasons to doubt this conclusion. Labour’s results were less impressive than those preceding the 1997 General Election landslide, but substantially better than any since the party went into opposition in 2010.

Figure 3: Labour lead over the Conservatives in projected vote shares since 1997

Firstly, it’s important to put national projections into context. As the Beyond The Topline blog wrote before the election, there are a number of structural reasons why the Conservatives overperform national polling in local elections. Differential turnout is likely to favour the Conservatives. Its councillors have historically been able to weather unpopular governments surprisingly well. Meanwhile, Labour voters are less likely to turn out and more likely to vote for the Liberal Democrats at a local level. These factors explain why a 7-9% Labour lead in the local elections is consistent with a much larger Westminster lead. Indeed, a 7% lead in NEV is the largest since 2001 while 9% in PNS is the largest since 1997 (see Figure 3), both General Election years in which Labour won landslide victories.

Looking at local elections the year before a General Election, for periods where Labour has been in opposition since the 1980s, Labour’s lead in 2023 is the largest aside from 1997. It is substantially larger than any other set of local elections, all of which preceded a Labour General Election loss. History is not deterministic - a lot could change in the next year - but by placing the national projections in context, we see no reason to doubt Labour’s General Election viability.

Secondly, there are good reasons to question the use of “Uniform Swing” in this case. A key characteristic of the 2019 General Election was the efficiency of the Conservative vote, winning a majority out of proportion of its vote share. Labour, by contrast, was very inefficiently distributed: winning huge majorities in urban centres while losing narrowly in key seats across the country. Uniform swing rests on this electoral geography staying relatively stable. While that is a reasonable assumption using national polling, it does not reflect what we saw in the local elections.

Labour was effective in its targeting, and won far more councillors than you would expect from uniform swing. We can see this reflected in constituency-level results, tallied by the New Statesman, which show Labour winning Westminster constituencies with large Conservative majorities. The party has focussed its attention on working class Leave voters, who are much more efficiently distributed than Labour’s Remain-voting 2019 coalition. Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats and Greens made gains in Labour’s unwinnable areas, as well as safe Labour seats - in Liverpool, Manchester and Tyneside - making the Labour vote more efficient.

Table 1: NEV, PNS and General Election results since 1983

The rise of the Liberal Democrats and Greens expose another weakness with translating local election vote shares to Westminster. Nobody expects that the Lib Dems and “Others” will take 35-40% of the vote in a Westminster election, so winning these voters will be key to the next General Election. As a group, they are much less favourable to the Conservatives than in previous years. Liberal Democrat voters in particular are much more favourable to Labour now. Polling published in The Times suggests that 23% of Lib Dem local election voters will switch to Labour at a General Election, compared to only 9% for the Conservatives. If Labour can persuade more Liberal Democrat and “Other” local election voters than the Conservatives, they will be on course for victory.

Taken together, these local elections paint a negative picture for the government. While Labour’s results are less impressive than those preceding the 1997 landslide, it is clear that the party is in its strongest position since leaving government in 2010. While much could change between now and the next election, the local election results are consistent with a Labour Party on the path to a majority.

Can Labour avoid a repeat of 1992?

Figure 4: Average opposition lead in opinion polling by days to the election, grouped by whether or not the opposition won the election in question

As multiple Conservatives pointed out on election night, mid-term local elections and polls can be an opportunity for voters to punish the government before ultimately returning at the General Election. Conservative hopes, and Labour fears, are pinned on memories of the 1992 election, which Labour unexpectedly lost despite a substantial polling lead in the preceding Parliament. To consider these claims, we have analysed polling data going back to 1955. Figure 4 shows Labour’s polling lead in this Parliament, compared with the average winning and losing opposition parties from previous Parliaments. Shown this way, we can see clearly that opposition parties tend to perform better between 1,000 and 500 days before the General Election, suggesting that Labour’s lead could narrow in the next year or two. However, Labour’s lead is still larger than the average winning opposition at this point, leaving the Conservatives with an uphill struggle to the next election.

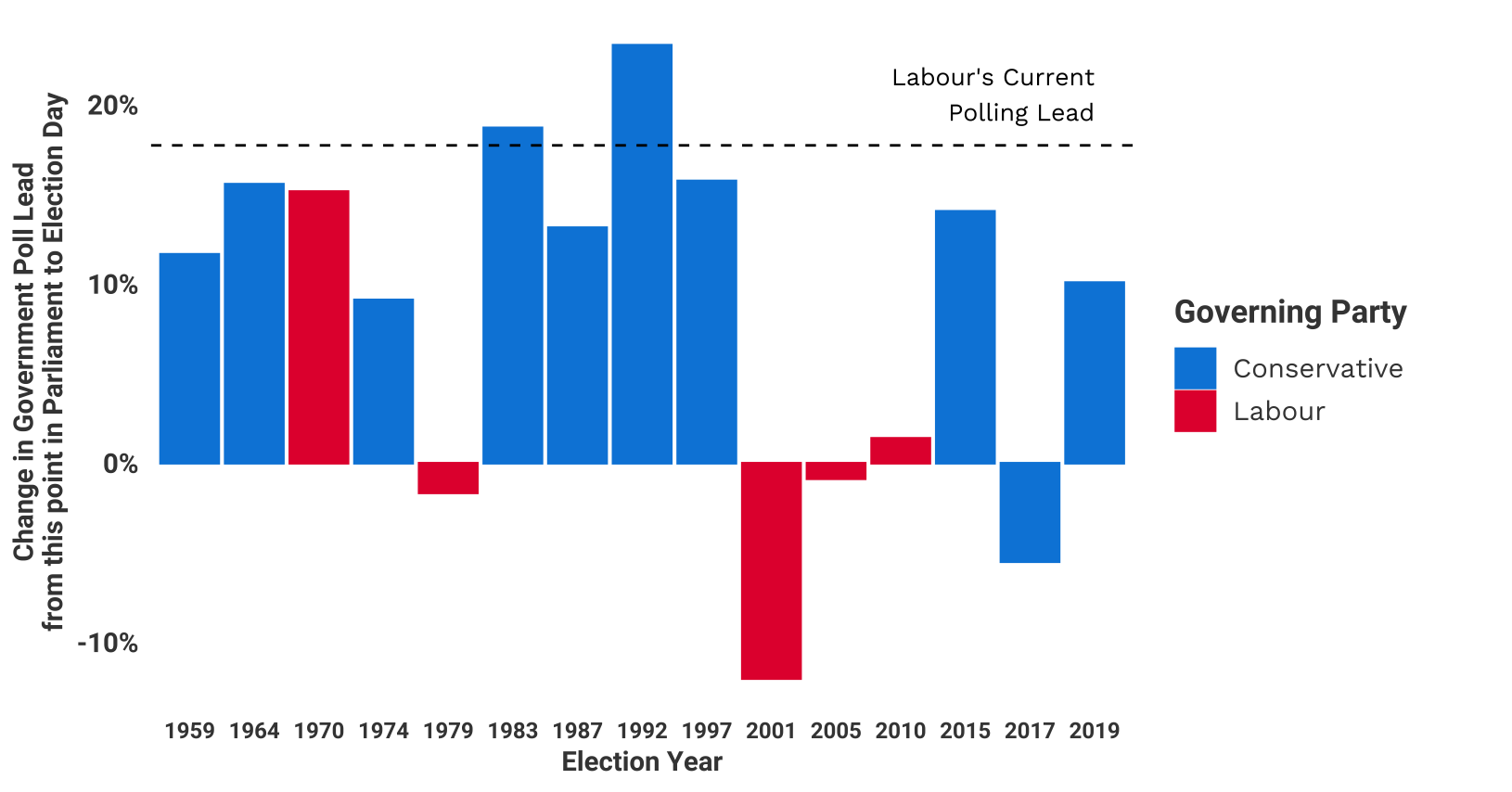

Figure 5: Historic recoveries for governing parties from this point in the Parliament

In 1992, the problem was two-fold. National polling narrowed as the election approached and the Conservatives significantly outperformed polls on election day. In Figure 5, we take possible polling errors into account, comparing the opposition poll lead at this point in the Parliament to the true results. As we can see, 1992 stands out. If a 1992-style surge for the Government materialised, the Conservatives would win the next election. However, 1992 is unusual. It is the largest recovery for any government since polling began. A recovery like the Conservatives received in 2015 or 2019, for example, would not be sufficient to win the popular vote.

It is also worth considering why polling tends to narrow as the election approaches. In 1992, the turning point for the Conservative government was Margaret Thatcher’s resignation. But while Thatcher was a drag on her party’s popularity in 1990, Sunak is likely an asset. Instead, the Conservatives are pinning their hopes on falling inflation and a growing economy. Improving economic conditions contributed to Conservative polling recoveries in 1983, 1987 and 2015. But with approval of the government’s handling of the economy currently at -52%, there will have to be a major turnaround for the Conservatives to have a chance of staying in Number 10.